EXCERPTS

A year ago, my husband Matt and I crammed our son, our dog, and everything else we could fit into our car and drove to my in-laws’ in southwest Virginia. New York hadn’t yet shut down, but I’d become acutely aware of how many surfaces my son, Cy, managed to touch, despite my best efforts, every time we left the house. When I imagined trying to work if his preschool closed, I considered how recently, left briefly unattended, he’d stuck his finger in a socket purely because he was curious why I was always telling him not to. (“There is a bee in there, Mama!” he cried. “And it bit me!”) Matt and I had work we could do remotely. My in-laws had a basement full of toys and a fenced backyard.

We were there four months, during which the freelance work I’d lined up before quitting my job a month earlier pretty much evaporated. Financially, we were OK. Matt made more than me, and his job provided our health insurance. My in-laws also helped with Cy, as did Matt, and I had a lot more time right as Cy needed a lot more care. We were, in other words, wildly, unfairly fortunate. And yet, more than once, driving Cy around for no other reason than to get out of the house, all it took was the classic rock station playing Aerosmith’s “Dream On,” absurdly enough, to make me burst into tears.

When I started talking with women about what the pandemic has been like for mothers about two months ago, the conversations were often, for me at least, comforting. The politicians, domestic workers, actors, journalists, and entrepreneurs I interviewed weren't necessarily a representative group. The majority were able to work from home full-time, for example, and even those who didn’t at least had the bandwidth to talk to a reporter. “One of the reasons I can do this interview is I’m one of the lucky ones,” said Laura Gonzalez, a nanny in Seattle with a 14-year-old son.

The nature of the crisis, though, is that whatever the circumstances, almost everyone has been impacted. “People have long been able to buy their way out of these binds,” said Amy Westervelt, author of Forget “Having It All”: How America Messed up Motherhood and How to Fix It. “During the pandemic [being privileged] helped. But it hasn’t inoculated people as much as in the past.”

There were so many commonalities and these bolstered me, though they also offered a somewhat grim solidarity. We all loved our children with an all-encompassing abandon that existed beyond language or explanation. We were exhausted, disoriented, and doing our best, even if this occasionally involved a level of benign neglect. California State Assembly Member Buffy Wicks, a mother of two who received national attention when, upon learning voting couldn’t be done virtually, she brought her newborn to the statehouse, told me she’s never been more dependent on screen time: “Which I feel guilty about. But you're just like, ‘We're surviving.’” And I was glad I was not the only person to get off a call to find my son had destroyed the house in a manner I wouldn’t think a person his size was capable. “I have made the house bizarre!” he shouted with proud glee.

But the interviews could be horrifying, too. It was upsettingly common to feel we were falling short in every area of their lives — as parents, in our work, in our relationships. “My partner was like, ‘Let’s find time for us,’ but that’s on the bottom of the list right now,” said one woman who asked I not name her if I quoted her on the topic of her relationship. There was so much anger, shame, and sadness. “A woman who’s working and has three kids under the age of 5 told me, ‘I try to find two minutes out of a day where I can go in the bathroom to cry,’” said Wicks. Discovering that your work — in or out of the home — isn’t valued can be “shocking and hurtful and frankly traumatizing,” said Ai-jen Poo, the co-founder and executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

Discovering that your work — in or out of the home — isn’t valued can be “shocking and hurtful and frankly traumatizing.”

How is it that we still have a child care system that, unless you’re wealthy, only really works for families with a full-time, stay-at-home parent, when this hasn’t been the norm for decades? “Ever since having children, I’ve felt I was verging on crisis in perpetuity,” said Carmen Winant, an artist and professor. “The pandemic just exacerbated an already strained situation.” How is it that even as mothers’ experiences during the pandemic have begun to receive attention, it still seems to be something women discuss among ourselves? “Where are the men?” said writer Nina Renata Aron. “There is an absence of even virtue signaling. I kind of can’t get over it.”

What I also heard, though, was that this period has opened a window of possibility. “You know how at a 3D movie they give you those glasses, and all of a sudden everything is multi-dimensional?” said Poo. “I feel like the pandemic has allowed us to see that we’ve been depending on an invisible care infrastructure upheld by women, particularly women of color, and without it, everything collapses. This is the biggest opportunity in generations to reset our systems and policies. ... We have to cement the awakening.”

Many of the policy experts I spoke with shared Poo's sense of opportunity. Where does their optimism come from? “It has to do with the consciousness-raising happening among women and the linking of the experiences of corporate moms, frontline workers, and low-wage moms,” said C. Nicole Mason, president and chief executive officer of the Institute for Women's Policy Research. “All the low-wage workers who used to be invisible to us, from farm workers to grocery store workers to delivery workers — now we call them essential,” Poo said. “I think that’s huge.”

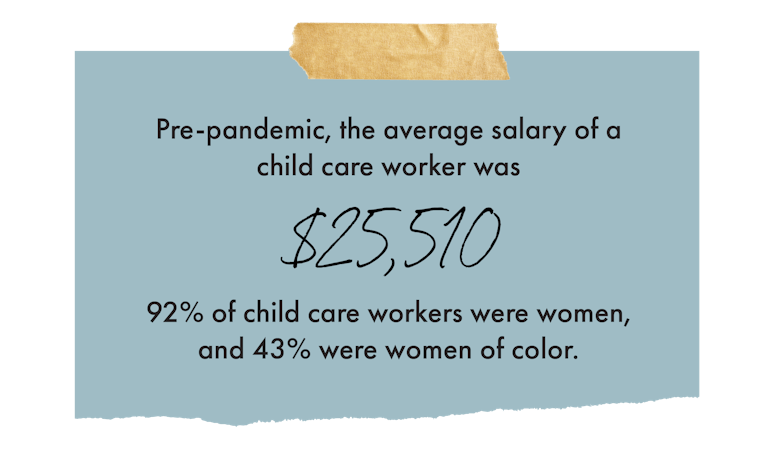

The United States puts far less public investment into early child care and education than other developed countries, and as a result, access to it is spotty and costly. The child care industry’s profit margins are such that it pays low wages, leaving many child care workers — 92% of whom are women, around half of whom are mothers of children under 18, and 40% of whom are women of color — struggling to afford child care themselves. Then there is the fact that the school day is shorter than most workdays, leaving parents (often mothers) struggling to fill in the gaps.

This is the biggest opportunity in generations to reset our systems and policies. We have to cement the awakening.”

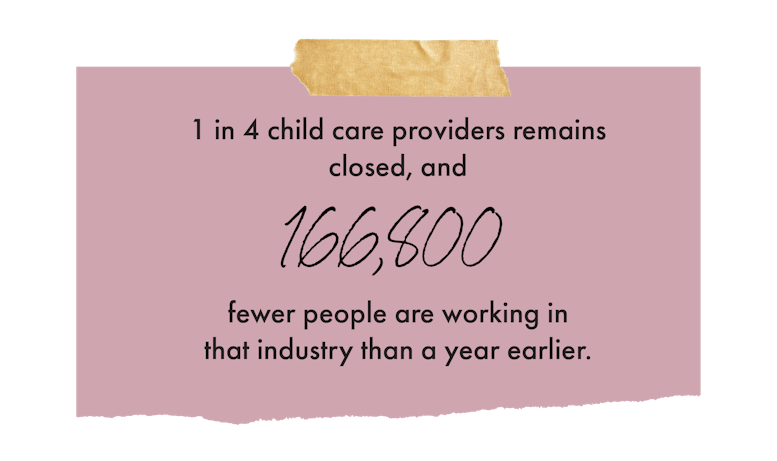

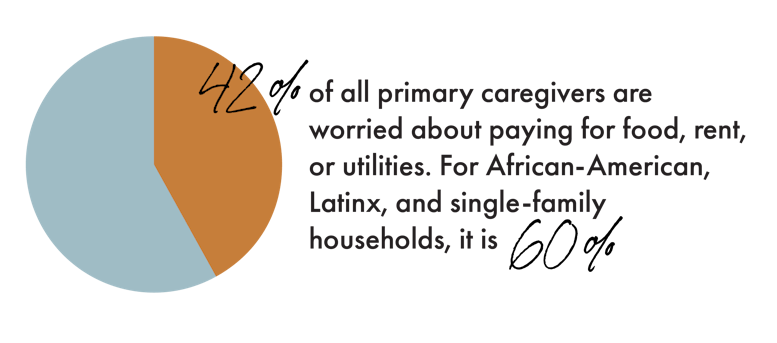

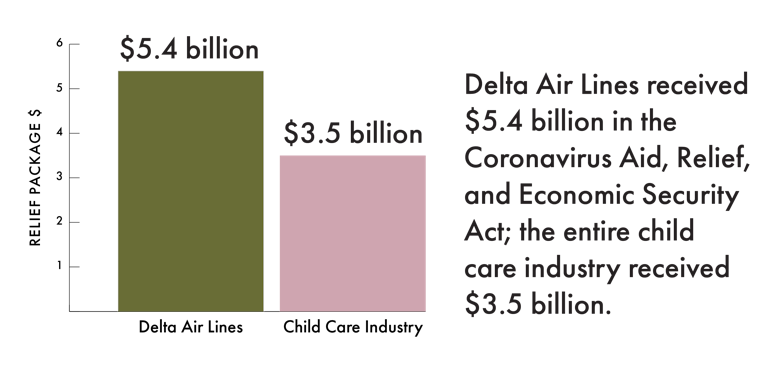

At this point, though, “it would take a lot [of investment] to get back even to what we had before the pandemic,” said Shana Bartley, the director of community partnerships at the National Women’s Law Center. If we don’t publicly invest in the child care industry and the women, largely Black and Latinx, who lost jobs during the pandemic, she said, “economic growth will be stunted for a long time, the cost of child care will be higher, and there will be communities that virtually don’t have any.” Or as Poo put it, “Every inequity would be exacerbated.”

The changes the experts I spoke with want to see implemented — child care infrastructure, paid sick leave for caregivers, a higher minimum wage, economic impact payments — are not new ideas. “What’s energizing is they were not on the table a year ago,” said Mason, though she, like others, takes nothing for granted. “Biden had the most aggressive platform that we've seen in presidential history on these issues,” said Wicks. “I'm hopeful. But I also recognize the only way we get it done is if we push people, and change is uncomfortable. So that's what we have to do.”

Of course, not everyone agrees about the scale of change that’s necessary. Mace, for example, acknowledges that the pandemic has exposed cracks in the system, but would prefer these be addressed through tax cuts and targeted expansions of preexisting government programs. “I’m a limited government, conservative type of person,” she said. “I have a lot of trust in the free market.” But among those who support broader interventions, there is a sense that the goal posts have shifted. “We’ve had someone like [Republican Senator] Joni Ernst calling for $25 billion for child care support,” Bartley said. “We’re seeing unprecedented numbers from the other side.”

Proponents of a universal child care system — which would cost closer to $50 billion, Bartley estimates — argue that, over the long-term, it’s a more efficient use of tax dollars. “Children who [participate in early childhood education programs] do better over their lifespans in terms of education, employment, and health,” said Lauren Kennedy, co-founder of the nonprofit Neighborhood Villages, which aims to improve access to affordable child care. “We have evidence of this; it pays off, and it’s doable.”

We’ve also done it before. The first, and only, time the United States has had a subsidized national child care program was during World War II, when so many men were overseas fighting that encouraging women to join the workforce was considered a national priority. Federal and local governments funded around 3,000 child care centers that cared for more than 500,000 kids over the course of the war. The programs, many of which were open 365 days a year, had low student-teacher ratios and enrichment activities, and they cost parents $10 a day (in today’s dollars). They were far from perfect — the funding was supposed to be granted without consideration of race or class, but the facilities were not always run this way.

Still, they were so popular that when news broke that they were to be defunded near the end of the war, the ensuing outcry led the plan to be delayed. They were finally shut down for good in 1946. Today, they’re a reminder of what the government is capable of when women’s work is deemed valuable.